The site of Beechworth’s police station and old gaol has an earlier history as the site of the Commissioner’s Camp: the administrative hub from which representatives of the government attempted to enforce the rule of law on the gold diggings — not always with the greatest success.

As I’ve been writing this blog, I’ve carefully skirted around one fundamental daily aspect of the Spring Creek and Reid’s Creek diggings: its administration by the colonial government. This is because the relationship between the miners and their administrative overlords was complex in ways that, I would argue, haven’t been properly accounted for by any historian to date (at least in the case of Beechworth), but which we know resulted in political agitations that contributed to the common man being granted the right to vote in the colony of Victoria by 1856. However, in mid-November 1852, when the Camp itself was being set up, its occupants had no way of knowing the role they would play in future events.

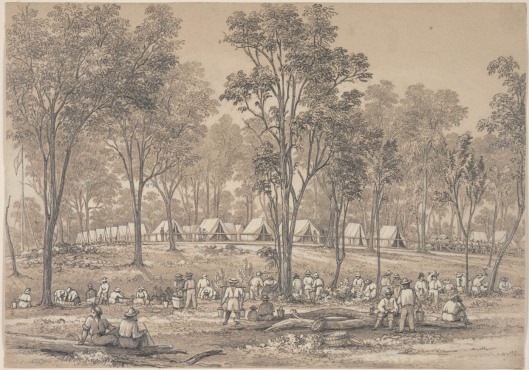

The Commissioner’s Camp, Spring Creek diggings, May Day Hills, drawn by Edward La Trobe Bateman, December 1852.

For the purposes of this blog post, it is enough just to explain the Commissioner’s Camp itself: what it was, who was there, and what they thought they were up to; and to look at some of their immediate troubles.

First, some background

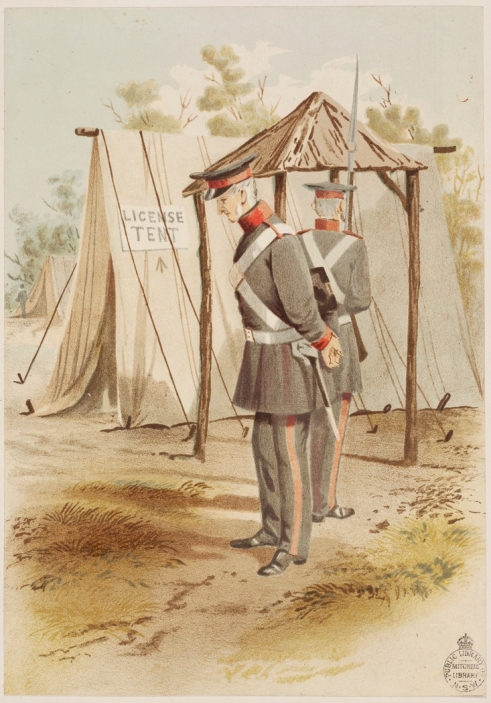

When the Victorian gold rushes first hit, the colony of Victoria had been only freshly carved-out from New South Wales. Its newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor Charles Joseph La Trobe and his inexperienced government were in complete shock when they suddenly found their quiet and remote colony invaded by thousands of gold seekers from across the globe. Nevertheless, they swiftly developed a system for administering the various goldfields, which was fashioned after the existing administration of the pastoral districts. This administrative system enabled the government to police the various diggings; provide and oversee official armed escorts for gold to Melbourne; provide an official means of registering and settling disputes over mining claims; and to tax the miners through a licensing system (the fee being initially set at 30 shillings per month, later reduced to £1 per month).

The miner’s license was extremely unpopular among the gold seekers. It was a regressive tax in the sense that it had to be paid before mining commenced, and therefore bore no relation to the ability of a miner to pay. Moreover, the tax was imposed on men who, generally lacking in property rights, had no corresponding right to vote under the existing political system. The miners expected, at the very least, to see their licensing fees fund amenities and services for the diggings, but for largely internal political reasons, the government was noticeably slow to fulfil these obligations. And finally, the antagonism over the licensing system was further exacerbated by the fact that it was often enforced by inexperienced, incompetent, sometimes heavy-handed and not infrequently corrupt officials and police; their activities summarised by digger Edward Ridpath:

‘the injustice of this impost [i.e.: the license fee] is great enough but the manner of its enforcement is even more so, at Bendigo men have been shot when running away form the police, others have been chained to logs, in cases where diggers have left their licenses at home they have not been allowed to go and fetch them, but at once marched off to the Commissioners and fined 5 pounds for not having them on their persons, for this service Government employs a body of men called the gold foot Cadets, a kind of nondescript policemen, they are principally young men of overbearing dispositions’ [1]

Licensing tent, Collection of lithographs and sketches, 1853-1874 by Samuel Thomas Gill, State Library Victoria. (Depicting a scene at Ballarat or Bendigo).

The Commissioner’s Camp, Ovens diggings — Who and what was there?

As soon as it became apparent that the Ovens diggings would be a goldfields of some significance, the government followed the procedure already developed to administer earlier-established diggings such as those at Ballarat and Bendigo, which was to establish an official encampment there. Organisation of this camp commenced with official appointments beginning in mid-October 1852. One of the earliest appointments was the man who would be Commissioner, James Maxwell Clow (1820-1894). Clow was charged with raising his own police force for the camp, and as the son of a Scottish Presbyterian Minister he seems to have selected a disproportionate number of Scotsmen for the task. [2] The Camp would be headed by a Resident Commissioner in the form of Henry Wilson Hutchinson Smythe (1815-1854), who left his base in Benalla (where he had already served as Commissioner of Crown Lands for the Murray district for close to a decade), especially to take up this new role. Known as ‘Long Smythe,’ (he was a commanding 198 centimetres tall), Smythe had started in the government service as a surveyor and cartographer, and though still in his mid-30s, he was a man of considerable experience. Worth pointing out is that technically, a ‘Commission’ was a royal appointment, so in a symbolic way, the Commissioners embodied sovereign power.

In terms of personnel, the earliest official appointments for the Commissioner’s Camp — appointments which continued through late October and into early November 1852 — were, in addition to the Resident Commissioner and Assistant Commissioner, their Clerk (J. LaTrobe); an Assistant Colonial Surgeon and Coroner (Dr Henry Greene); Police Magistrate (George Mitchell Harper) and his Clerk of the Bench (William Alexander Abbott); as well as Store-keeper (W. H. Agg). [3] There were also Mounted Police and Foot Police (also known as ‘Cadets’), headed by Lieutenant Templeton and Mr Mackay (rank of ‘Subaltern’) respectively. [4]

Resident Commissioner Smythe arrived on site on the Friday 19 November, 1852, where he found the camp in the process of being ‘judiciously pitched’. [5] Much of this was owed to the efforts of Assistant Commissioner Clow (who previously had been an Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands, and Assistant Gold Commissioner at Bendigo Creek [6]) and his newly appointed tent-keeper William Murdoch. It seems that Clow had arrived practically in advance of almost every other official, as a letter in the Argus dated 1 November, reported,

Our Commissioner, J. M. Clow, Esq., has arrived without any force that I have yet heard of; but it matters little, they are not, or rather have not been required in our community; a more quiet, orderly, set of diggers are not to be found assembled in Australia. [7]

Having been appointed in mid-October [8], Clow had made some arrangements for the Camp in Melbourne [9]. His tent keeper and personal attendant, William Murdoch, arrived at Spring Creek on Monday 15 November, and immediately erected a large tent for the store. Murdoch then spent the whole of Tuesday pitching tents, setting the Commissioner’s tent to rights the following day, and witnessing ‘Most of the men employed in putting up tents’ on Thursday before Smythe’s arrival on Friday. [10]

The Camp itself was situated on a slight rise above Spring Creek (‘a rising hill covered with flowering shrubs and stringy bark trees’ [10b]) facing onto a track (possibly of indigenous making, and almost certainly used by David Reid’s shepherds, as a shepherd’s hut was located nearby [11]), that would become modern-day High Street. The encampment spanned roughly the frontage from where the current police station is sited, across Williams Street to the frontage of the old Beechworth Gaol. [12] The location in official correspondence was ‘May Day Hills’: the name given to the area by Governor LaTrobe, who had visited the infant diggings on May Day earlier that year. [13]

Author William Howitt described the established May Day Hills Camp when he visited about a month later:

The tents of the Commissioners stood in a row, on a rising ground on the other side of the creek, with a number of other tents for servants and officials behind them. The whole was enclosed with post and rails, and sentinels were on duty as in a military camp. The Commissioners’ tents, lined with blue cloth, and of a capacious size, looked comfortable and, to a degree, imposing. Mr. Smythe, Commissioner of Crown Lands for this district, as well as a gold commissioner, and Mr. Lieutenant Templeton of the mounted police, received us most cordially… They had a good packet of letters for us, which we soon returned to our tent to read. [14]

Other tents erected in the Camp included a Mess tent (where Protestant religious services were also held), and two Hospital Tents (the only tents besides the Commissioners’ tents which were lined). [15] By early December, there was also a flagstaff, where, as Murdoch recorded in his diary, the men ‘got the Union Jack hoisted on the camp which here waved for the first time and I warrant as gaily as ever” on the land of the brave and the free”.’ [16]

Diggers and Commissioners, Order and Disorder

It had been already noted (in the popular press at least) that prior to the arrival of the Commissioners and their police on the Ovens diggings, ‘a more quiet, orderly, set of diggers [were]… not to be found assembled in Australia’. As historian David Goodman leads us to understand, this proclamation of a naturally high degree of ‘order’ on the diggings was not mentioned casually, but rather, the idea of ‘how order could be maintained in a society in which all were rushing, madly, after their own fortunes,’ was one of the major cultural themes of the gold rush era (in both California and Victoria). Funnily enough, this frequently included the assertion that ones’ own countrymen possessed an innate instinct for creating an ordered society when compared to the other: Victorians perceived respect for British law and institutions, and deference to existing social and political hierarchies, as constituting ‘order’, in preference to the Californian tendency towards independent self-organisation and self-governance, which in turn Californians perceived as a more worthy form of ‘order’. [17] Whatever the case, when the Commissioners and their police finally arrived on Ovens diggings in November 1852, their presence would test the supposed natural order of these diggings.

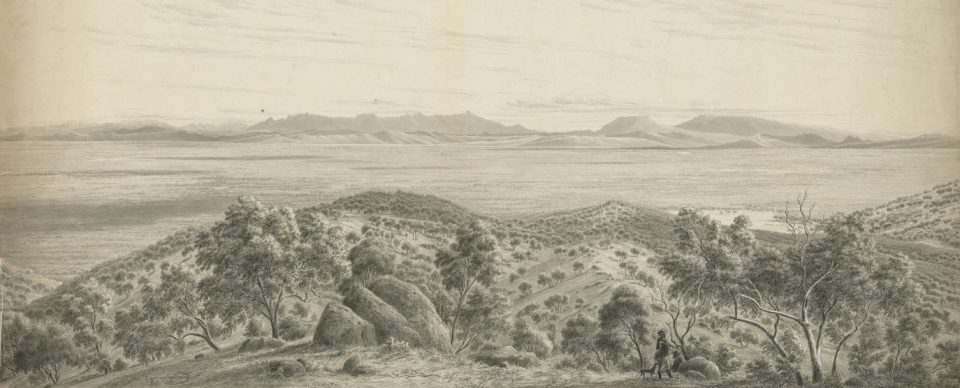

Having arrived on Friday, by Saturday 20 November 1852, Smythe was writing his first report to the Colonial Secretary (which he would be called upon to do weekly, along with submitting license returns for the same period). Clearly he had been asked to decide upon arrival which buildings should be erected before winter, and he judged that only a ‘lock-up’ or ‘watch house’ was required, along with stables for about 30 horses. Smythe added that Clow estimated the population of diggers to be 1500, adding, ‘The diggers are spreading more over this Country, and a very rich spot has been opened up about one mile above the original Diggings [i.e.: possibly Madman’s Gully or Beeson’s Flat]; which His Excellency visited on the 1st May last and about four miles below the present Diggings [i.e.: Reid’s Creek].’ [18]

Smythe’s first report on that Saturday 20 November also revealed that internally, the administration of the Camp itself was not yet in order: The Police Magistrate had arrived on Wednesday, but in the absence of official paperwork, couldn’t be sworn in; the Doctor had arrived on Friday (the same day as Smythe), but as the medicines he had applied for had not yet arrived from Melbourne, he couldn’t begin to treat anyone. Mackay had also arrived, stating that he was to be Superintendent of the Foot Police, but there was no paperwork to back his claim. (Only upon further investigation by Smythe was he found to hold the lesser post of Subaltern). [19]

However, despite the internal disarray, Smythe was initially satisfied with the external order of the diggings. ‘I am happy to state,’ he wrote, ‘that good order prevails tho’ a number of bad characters are reported recognised as having been known at Bendigo.’ [20]

It all seemed promising enough. However, it only took until Monday (22 November), a mere three days after his arrival, that Smythe’s satisfaction switched to misgivings about the capacity of the Camp to enforce the rule of law. To the Colonial Secretary, he now wrote:

I find the police force at present stationed here quite inadequate for protection of life respectively in the want of their being called upon to act. Men in abundance could be hired here, in fact I am endeavouring to procure some – but they will be of little use with out arms, accoutrements and some sort of uniforms, however simple — The latter should at the same time be of the best quality – under these circumstances I beg to recommend that twenty men should be hired armed, clothed and accoutred in Melbourne and forwarded up on the command of a Sergeant. – These with the nine present on the ground and the additional Gold Police which I understand are on the road will for the present be sufficient. [21]

So what had happened that Monday after Smythe’s arrival to so rapidly change his opinion of the ‘orderliness’ of the diggings? The Reid’s Creek diggings had opened up earlier in the preceding week, so in purely geographical terms, the administrative problem had doubled almost overnight: just as one camp was being established at Spring Creek, a second camp was urgently needed four miles away at Reid’s Creek. [22] More importantly, the population of the diggings was growing at a rate of about hundred and twenty-five new diggers each day. [23] And now that the Commissioner’s camp was operational, the gold cadets had begun patrolling for licenses and had proved diligent in their efforts: the same Monday as Smythe sat down to compose his letter to request more police, ‘Twenty one diggers [had been] fined for want of licence[,] some paying others not. Perhaps for want of money but ultimately paying a £3 fine and taking a licence.’ [24] As many of the newly-arrived miners had slender financial means, the newly-arrived police force, with their increased license patrols, would have been a source of great discontent on the diggings. When Smythe wrote, I find the police force at present stationed here quite inadequate for protection of life, he meant protection of his own life, and the life of anyone attempting to collect license fees from angry and well-armed miners.

The level of discontent quickly came to a head. 12 more diggers were fined the very next day, two of whom were kept in custody, [25] and although we cannot say for certain under what conditions these miners were held, it was rumoured that they were chained to a tree. [26] This constituted too much of an affront to the miners who on Wednesday evening, held meeting attended by ‘nearly 800 diggers’, at which they discussed how to respond to their ill-treatment at the hands of the Commissioners and their police. [27] A reporter, writing for the Argus newspaper from the Royal Hotel in Albury, described the meeting:

The organ of this heterogeneos assembly was either a Yankee importation from California, or an Anglo-Australian, who had visited that part of the world. He recommended, in no measured language, the protection of all persons sought to be taken into custody by the police for an infraction of the law, and the repelling, if necessary, of force by force. [28]

In describing the meeting, the journalist clearly flagged the Californian influence on the diggings, which in the Australian popular press was equated with violence, gun-play and Republicanism. Simultaneously, the author acknowledged that the constituents of the diggings were heterogeneous — that is to say, diverse — presumably not only in their backgrounds but also in this context, political leanings. (However, rather than use the English word, the writer employed the Spanish word heterogeneos, just to further call the Californian influence into view.). [29] While the article was disparaging of Californian attitudes towards challenging authority — attitudes which had little respect for the law or established institutions — neither did this mean that its author sided with the Commissioners. They sided with the heterogeneos — that diverse and politically unrepresented group, the diggers.

The miner’s meeting would set the scene for the events of the following day (which I have recounted in the recently revised post Diggers Rise Up), which would be the first instance of civil unrest on the Ovens diggings, and which in turn helped forge new political expressions that were fundamental to the growth of Australian democracy — a subject matter which will have to be unravelled in future posts.

To read the basic facts of what happened the next day, try reading Diggers Rise Up, a precursor to the Eureka Stockade.

Notes

[1] Edward Ridpath, Journal, transcription of letters to his father, possibly in his own hand, 1850-53? [manuscript MS 8759], State Library of Victoria, Box 1012/4 [Box also includes his gold license from 3 August 1853], p.37

[2] William Murdoch, A Journey to Australia in 1852 and Peregrinations in that Land of Dirt and Gold, unpublished diary manuscript (digital form), held by the Robert O-Hara Burke Memorial Museum. That Clow raised his own police force (18 October, 1852: ‘he was obliged to raise his own men – that is mounted police and foot’), and that there were a lot of Scotch men appointed (15 November 1852).

[3] Appointment listed in: 1853 Victoria, Gold Fields: Return to Address, Mr Fawkner — 10th Dec 1852, Laid upon the Council Table by the Colonial Secretary, by command of his Excellency Lieutenant Governor… printed 27 Sept 1853, Victorian Parliamentary paper; and reported in Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, Sat 6 Nov, 1852, p.2 (drawn from The Government Gazette of Thursday (ie: 4th November 1852).

[4] These appointments are obvious from numerous correspondences and reportages.

[5] Public Records Office Victoria, Series VPRS 1189, Consignment P0000, Unit 83, document 52/8477.

[6] Goldfields: Return to Address, December 1852, op. cit.

[7] The Argus, 4 December 1852, p.5, from a letter dated 1 December, 1852.

[8] Goldfields: Return to Address, December 1852, op. cit.

[9] William Murdoch, op. cit., reports seeing Clow in Melbourne on the 23 October.

[10] William Murdoch, ibid., 18 November, 1852. [10b] William Murdoch, ibid., 15 November, 1852.

[11] David Reid, Reminiscences of David Reid : as given to J.C.H. Ogier (in Nov. 1905), who has set them down in the third person, 1906, p.54.

[12] Plan of the township of Beechworth, May Day Hills, Surveyor General’s Office, Melbourne, July 23rd 1855. (Map, held in State Library of Victoria).

[13] Smythe mentions La Trobe’s visit on May Day in official correspondence (Public Records Office Victoria Series VPRS 1189, Consignment P0000 Unit 83, 52/8477), and it is also reported in The Argus, Saturday, 8 May, 1852, p.4.

[14] William Howitt, Land, Labour and Gold, Kilmore, Lowden, 1972, p.93-4 (contained in a letter from the Ovens Diggings, Spring Creek, Dec. 25th 1852).

[15] Letter to the Chief Commissioner of Police, Melbourne, from Inspector Price, Acting Inspector of Police in charge Ovens district, Head Quarters Ovens Police Camp, May Day Hills, 8 April 1853. This is contained in: Beechworth District (May Day Hill) 1853 & 1856, Inward Registered Correspondence, Series VPRS Series 00937/P0000 000028, Public Records Office, Victoria. (Apologies for the lack of precise document number to identify this letter in what is otherwise a very big box of letters.)

[16] William Murdoch, op. cit., 3 December 1852.

[17] David Goodman, Gold Seeking — Victoria and California in the 1850s, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1994, pp.64-65.

[18] Public Records Office Victoria, Series VPRS 1189, Consignment P0000, Unit 83, document 52/8477.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Public Records Office Victoria, Series VPRS 1189 Consignment P0000, Unit 83, document 52/82175.

[22] To give an idea of how fast the diggings were expanding, Edward Ridpath, who arrived on the Spring Creek diggings on 4 November 1852, said of the diggings at Spring Creek, ‘I must confess to be being much surprised at their general appearance on my arrival, that their operations were confined to a spot of ground about one mile in length, and about a hundred yards in breadth’. (Ridpath, op cit., p.8-9).

Within ten days, another digger, Ned Peters (A Gold Digger’s Diary, typed manuscript of his diary, edited by Les Blake, MS 11211, State Library of Victoria, p.26.) recorded in his diary that when he arrived on the Ovens diggings, Reid’s Creek had opened-up only the day before. He’d departed for the Ovens diggings from Bendigo on 1 November 1852, and says he took ‘a fortnight on the road’ to reach the Ovens diggings, which puts his arrival around Sunday 14 or Monday 15 November. This meant that the focus of the diggings began to shift to Reid’s Creek within the exact week as the establishment of the Commissioner’s Camp at Spring Creek. Such was the force of the shift that the party of Thomas Woolner (Diary of Thomas Woolner, National Library of Australia, MS 2939, 25 November, 1852), another gold-seeker, who arrived at the diggings the same day as Smythe (Friday 19 November 1852), went straight to Reid’s Creek rather than stop for the night at Spring Creek.

[23] By 10 December, a mere 21 days after Smythe had arrived, the population of Spring and Reid’s Creeks had grown from 1500 to 4000; 2500 were at Reid’s Creek, four miles from the Commissioner’s Camp. While Clow estimated 1500 people between the two diggings in mid-November, by the first week of December it had swelled to 1500 persons on on Spring Creek (which by then was being referred to as ‘the old diggings’), and a further 2500 at Reid’s Creek. (population figures contained in The Argus, ‘Scraps from the Ovens,’ Friday 10 December, 1852.)

[24] William Murdoch, op cit., 22 November 1852.

[25] William Murdoch, ibid., 24-25 November, 1852.

[26] Edward Ridpath alludes to police chaining people to trees (as cited earlier in this piece, op. cit., p.37), and this is backed up by a ‘rumour’ in The Argus, ‘Disturbances at the Diggings’, 1 December 1852, p.4.

[27] The Argus, ‘The Ovens Diggings. (From our special commissioner.) Royal Hotel, Albury, Nov. 28th,’ 3 December, 1852, p.4.

[28] ibid.

[29] ibid.

Very interesting! Especially the links to California – I wonder how many of our diggers came from there? Of course the ideas would come no matter the number….

LikeLike

There were quite a few who’d been to California. Two of Beechworth’s most prominent 19th century businessmen were George Billson, who had been to California, and Hiram Crawford who was American.

LikeLike

Someone told me about a local who has done some research on Americans in Beechworth. I will have to find out who it is.

LikeLike

I have a cousin, Samuel Stackpoole Furnell (1823-1880), who was at Spring Creek as a sub-inspector. He was later at Eureka https://ayfamilyhistory.com/2017/12/02/my-cousin-at-eureka/

Regards

Anne

LikeLike

Thank you for this link Anne! I am interested in the links between people on the Beechworth diggings and the Eureka rebellion. I will note your work for later reference.

LikeLiked by 1 person